In this series of articles, Manuel Klein and Alexander Bechtel write about the fundamentals of our monetary system and what will change in the future with the introduction of digital money. Here you can find all articles of this series published so far. This article is about the money creation process. How is new money created? Who is allowed to create new money and what are the rules/restrictions? This article is about the creation of money of the central bank and commercial banks.

How are new cash and central bank reserves created?

Probably the best known and still widely used form of money is cash. Who generates it and how does it come into circulation? Cash is not created proactively by the central bank, but only when bank customers request it. The amount of digital money in the customer’s bank account is then „withdrawn“ and converted into cash. As banks hold only a limited amount of cash in their branches and ATMs, large withdrawals may require the bank to first convert reserve holdings at the central bank into cash.

For this reason, large withdrawals must usually also be announced to the bank. Once the cash has been withdrawn, the bank balance sheet is reduced, as the deposits are cancelled and the cash is held by the bank customer, and thus the bank no longer acts as an intermediary. It is important to emphasize that no new money is created in this process. It merely converts one existing form of money (giro money) into another (cash).

Financial crisis has changed a lot

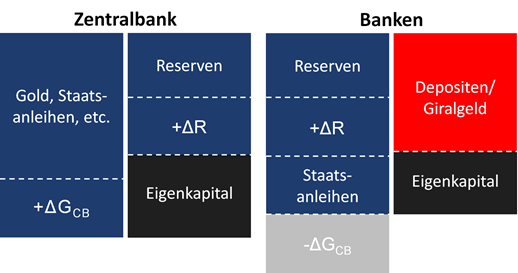

The central bank can create new central bank reserves at will. In the past, central banks only produced reserves when the customer (in this case: banks) demanded reserves – similar to cash today. However, since the 2008 financial crisis (in the Eurozone since 2015), central banks around the world have been proactively creating huge amounts of reserves through asset purchases (quantitative easing). As the balance sheets below show, money creation takes place through a balance sheet extension: assets (mainly government bonds, G) are added to the balance sheet on the asset side and reserves (R) on the liability side. The central bank creates the new reserves virtually „out of thin air“ and thus acquires the assets. The additional reserves thus enter the economic cycle, or more precisely, the banks‘ balance sheets.

However, central banks do this not to provide banks with more money to lend to economic agents and „non-banks“ but to influence long-term interest rates paid on government bonds in addition to short-term interest rates. The additional demand for the bonds raises their price, which leads to falling interest rates due to the inverse relationship between the price and yield of a bond.

Money creation: commercial banks‘ banknotes and coins

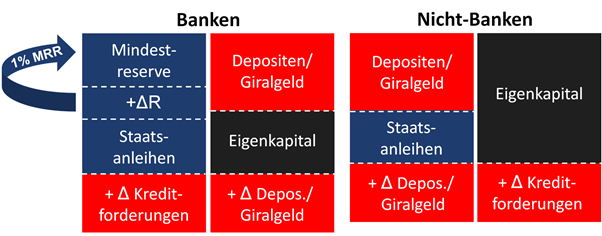

However, as described in the second article of our series, the bulk of the money supply used as a transaction and store of value is created by commercial banks – basically in the same way that central banks create money: via balance sheet extensions. This process is also shown below in the form of balance sheets – this time by the balance sheets of banks and non-banks.

Every time banks make a loan, additional money is created. Banks record the loan receivable on the asset side of the balance sheet and create liabilities due on demand on the liability side. These liabilities are the money that the recipient of the credit finds in his bank account (deposits, giro money). But banks can also create new money by buying assets, either financial assets like bonds or stocks, or real assets like real estate. This process is similar to the reserve generation process of central banks presented above.

Certain requirements must be met

In order for banks to create new money, they must hold a certain amount of central bank reserves. Currently, one euro must be held in reserve for every 100 euros of credit. There is therefore a minimum reserve requirement (MRR) of one per cent. The MRR must be met on average over the so-called reserve maintenance periods so that banks can also lend first and obtain the reserves later.

The self-generated liabilities of the banks, due on demand, are claims of the debtors or sellers of the assets, which give them the right to withdraw cash in the same amount, which is the only legal tender in the present system. What the „non-bank“ sector uses as money is therefore basically claims on commercial banks for the withdrawal of cash. To put it another way: We use vouchers on money as the main means of payment. This works well so far, because payments are ultimately settled in central bank reserves, and the fiat money can be exchanged for cash at any time.

Differences between money creation by central banks and commercial banks

Central banks have a monopoly over the creation of base money. They do not have to worry about liquidity outflows or outflows from other assets (such as gold) because there is no other asset to which their liability relates. At the time of the gold standard, things were different: central bank money was backed by gold and holders of cash could claim their claim on gold against the central bank. In other words, even though physical cash is still recorded as a liability of the central bank, there is nothing that the holder of cash can claim from the central bank. Therefore, central banks can buy unlimited amounts of assets and consequently create central bank reserves of the same nominal amount on their balance sheet without running into liquidity constraints or holding too little gold.

Do not print money indefinitely

Unlike central banks, however, banks cannot create money without limits. Firstly, banks must comply with the extensive Basel III rules, which define, among other things, capital requirements. Banks must hold a certain buffer of capital in relation to their (risk-weighted) assets. In other words, the deposits must not become too large compared to the equity.

Second, banks must meet the minimum reserve requirements mentioned above. Since the introduction of „full allotment“ in 2008, i.e. the possibility of refinancing with the central bank at any time, banks have been able to draw unlimited reserves from the ECB (against adequate collateral). The expansionary monetary policy of the ECB and other central banks after the financial crisis has also led to banks holding large amounts of excess reserves, which means that reserve requirements no longer represent a real limit and have even been abolished completely by some central banks in recent years. Finally, bank lending, and hence money creation, is of course also limited by the availability of creditworthy borrowers to whom banks lend.

Outlook:

In the next article, we’ll take another detailed look at why our money today is (mostly) a liability of an issuer and how that money differs from cryptocurrencies. The aim of the article is to understand the difference between digitized and digital money.

About the author: Manuel Klein is a senior consultant in the financial services technology consulting division of a big-four consulting firm. He helps clients understand how digital blockchain-based money differs from today’s existing forms of money, how banks should deal with Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC), and how they can develop their own blockchain-based payment solutions. He also brings expertise in the design and custody of digital assets and helps clients leverage this rapidly growing area.

Header image iStock Image credit: vaeenma