A guest contribution by Maximilian Fuchs

For many German merchants, the girocard as a low-cost, domestically accepted debit card system was and is a lifeline in the face of rising card acceptance costs. However, recent reports suggest that it is under increasing threat from mono-badge card issuing. With some of Europe’s national card schemes in retreat, we take an international look at the problem and ask how merchants can best take advantage of the current climate to protect themselves and their customers from rising payment costs.

The dangers of mono-badging

It is common for the average German consumer to carry a debit card showing the domestic girocard brand next to the logo of an international card scheme. These cards present merchants and consumers with a choice: process domestic payments via the girocard (with negotiable interchange fees), or stick with the global systems.

CMSPI projects with hundreds of merchants in Europe show that significant cost savings can be achieved by using the girocard system. Although the girocard can currently only be used for stationary debit payments, our analysis shows that it was responsible for 61% of German card transactions in 2020[1].

Mono-badging refers to cards that are equipped with only one system for processing the transaction. So with a card that is mono-badged, the choice is now eliminated and the transaction must be mapped through the existing system and no longer competes for merchant favor through payment acceptance costs.

Regulators around the world have recognised the negative impact this can have on competition. In the U.S., for example, the Durbin Amendment of 2011 mandated that all debit cards be equipped with at least two non-competing systems. Such mandates put brands in direct competition with each other on every map and have been shown to create sustained downward pressure on fees[2]. Australian regulators have also recently recognised the problem and, in a consultation undertaken, have proposed lowering the caps on interchange fees (paid to issuing banks) for mono-badged cards in order to reduce the issuance of these cards[3].

The trend in Germany

Reportedly, the rise of mono-badging began in Germany around 2015[4]. In the first phase, international card companies entered into agreements with German neobanks to issue debit cards bearing only their scheme, including, for example, N26[5] and C24[6]. Recently, the trend has spread to traditional banks as well. In August 2020, for example, Oldenburgische Landesbank announced an exclusivity agreement with Mastercard, which was accompanied by an agreement to issue the new Mastercard-only “ec card” – a name popularly used for cards with girocard functionality[7]. There are also reports of mono-badging at larger issuing banks, such as HVB, Comdirect and DKB[8] [9]. Such arrangements can range from exclusivity to the introduction of the international system as a “top of wallet” through the introduction of mono-badged cards alongside the banks’ traditional offering.

In the short term, these developments, in addition to causing higher costs, could harm merchants whose terminals are activated solely for the girocard and cause them to abandon this barrier to international card systems.[10]. In the long term, they could limit the reach of the girocard system as a whole.

What is happening all over Europe?

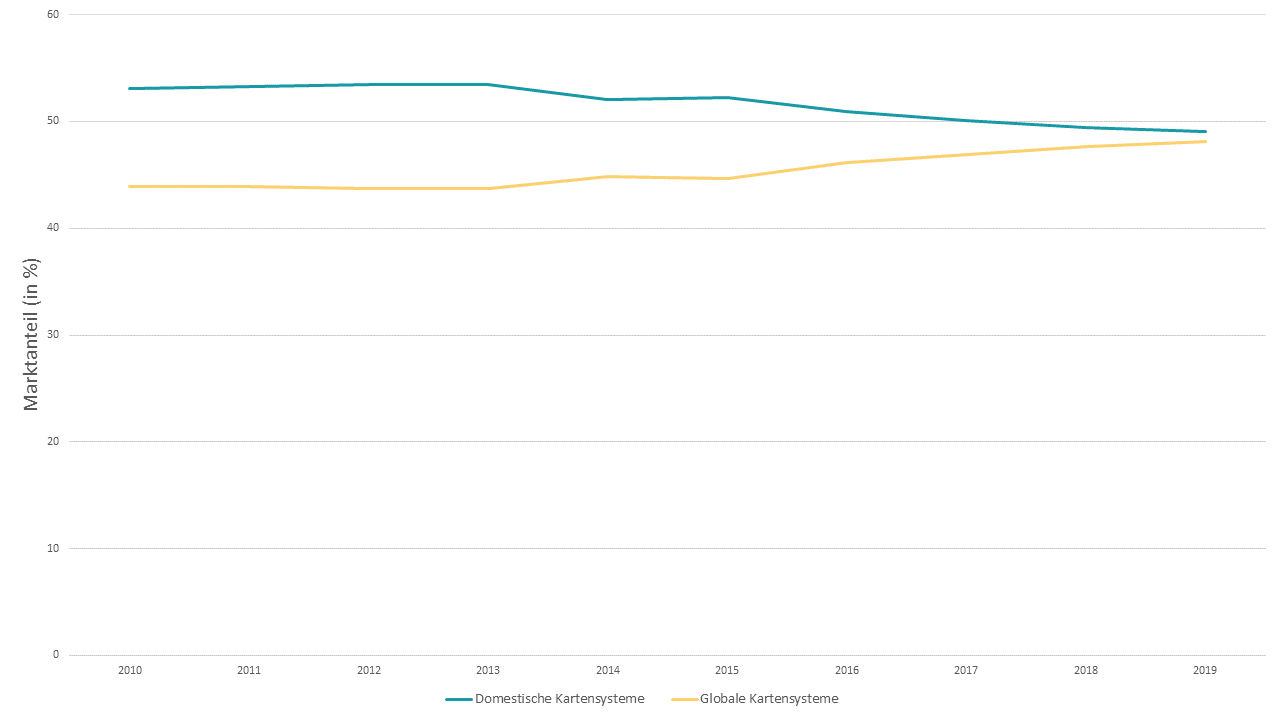

German merchants are not the only ones to enjoy the benefits of a local card system; France’s Cartes Bancaires, Italy’s Pagobancomat and Belgium’s Bancontact are just some of the systems that compete to a greater or lesser extent with international brands in their respective markets. However, past experience shows that the fate of a European card system is not certain. Several systems have been abandoned in the last decade, including Finland’s pankkikortti (2013), Ireland’s Laser (2014) and Luxembourg’s Bancomat (2011)[11]. In other countries, such as Spain, there is a domestically operated system, but it does not process card transactions, leaving this to the global systems with which they have collective agreements.[12]. Figure 1 shows the remarkable decline of domestic card schemes in Europe over time.

Figure 1: European market share by value (domesticated vs. global systems)

Source: CMSPI and Zephyre analysis based on data from Euromonitor International.

When a local system is displaced, the typical result is a market dominated by the two dominant international card systems. Without an alternative, traders are forced to deal with successive fee increases from international providers. CMSPI estimates that since 2015, scheme fee increases from global schemes alone have added more than €1.46 billion in additional annual costs to European traders[13] despite the presence of local systems, suggesting that their removal could exacerbate the problem.

Do innovations bring hope?

In the card industry, the European Payments Initiative (EPI) is often touted as the solution to the demise of local systems. A new pan-European card scheme could indeed provide much needed competition to the global players and seems to be strongly supported by the European Commission. Although the outlook for EPI is highly controversial, proposals show[14]The fact that EPI will completely replace local systems only reinforces the need for mandatory co-badging.

Fortunately, competition may not be the only option when it comes to card payments. In recent years, the proliferation of alternative payment methods across Europe has created new opportunities for merchants to manage the cost of accepting payments.

The Netherlands is a good example: While the local card system (PIN) 2012[15] abandoned, low-cost alternative remittance solution iDeal already accounted for 56% of the country’s online payments mix in 2019[16]. Similar progress is being made with Poland’s Blik and the development of instant payment systems such as SCT Inst. With these long-term trends in mind, the use of alternative payment methods – even those that are historically familiar, such as SEPA-ELV – is more important than ever for merchants who want to stay ahead of the curve.

However, alternative payment methods alone are not enough. Without a system that requires payment instruments to compete for merchant preference, alternative payment methods with proprietary user bases could lead to mini-monopolies and pressure merchants to accept even higher fees for a portion of their transactions. Apparent innovation can also have the opposite effect; in the case of the Nordic instant payment system P27, for example, Mastercard has already been selected as a key technology partner[17].

What can traders do?

So far, the girocard system appears to be holding firm, as its estimated market share has increased from 58% to 61% between 2015 and 2019[18]. However, mono-badging arrangements could pose a threat to the long-term viability of the girocard and to merchants who rely on the system to keep costs (and prices to consumers) low. A similar story has played out several times on the European stage. Because of this, it is important for merchants to lobby and advocate for co-badging regulations – similar to those in the US – as the plans for the European Payments Initiative are currently unknown.

Even if the girocard is able to maintain its dominance, the decline in cash usage in Germany has led to an estimated 30% increase in the absolute value of transactions processed by international card schemes in just four years[19]. CMSPI estimates that the average fees German merchants have to pay for these transactions increased by over 60% between 2015 and 2020. Given these trends, retailers are forced to find new ways to generate competition. These range from the use of new payment systems to the introduction of alternative payment methods that require a far more complicated business case than cards ever did. For German merchants, the current climate has therefore made a sophisticated payment strategy most relevant at precisely the time when it was most complex to build.

Sources:

1] CMSPI estimates and analysis based on Euromonitor International (2021) data.

[2] See CMSPI analysis of Federal Reserve Regulation ii Report

[11] Centre for European Reform (2021). Don’t imitate – innovate! Why Europe doesn’t need a rival to Visa and Mastercard.

[12] Comision Nacional de los Mercados y la Competencia (2018).

[13] See CMSPI & Zephyre Scheme Fee Study (2020).

[18] CMSPI estimates and analysis based on Euromonitor International (2021) data

[19] CMSPI estimates and analysis based on Euromonitor International (2021) data. 2015 – 2019