Introduction

Key digitization. A challenge that does not want to end. A complex topic, especially for companies that do their business mainly that do their business mainly in and around the internet. If they also offer services, it becomes particularly complicated. At the beginning of the millennium, the technology industry was in a veritable gold-rush mood. Everyone suspected that the establishment of the Internet and digital technologies would have a major impact on and change the economy in the future. The interest of investors was correspondingly high. Companies only had to take up the cause of “internet” and “technology” in order to achieve a high rating.

Digitalization is no longer, as it was 18 years ago, a future topic, but part of our everyday life, tangible, comprehensible. If the tech companies often had nothing more to show than a “.com” or “.de” in their name at that time, today the evaluations of the technology companies are based on real value. This value is measured in terms of customers, real sales and, above all, data, data and even more data.

And it is precisely this knowledge of the customer, coupled with the innovative ability of the tech groups and the will to constantly develop and grow, that forms the basis for the exponentially increasing stock market valuations.

With their influence, which is meanwhile so far advanced, the GAFA live the digital transformation per excellence. Whereas 18 years ago the “.de” or “.com” in the name cause the share price to rise, today it is something with coin, crypto or blockchain that is inspiring investors. What becomes clear from all this is that we are in the midst of one of the greatest digital changes and such a rapid transformation that some companies are no longer able to keep up with their digital transformation.

Jochen Siegert would like to explain in his successor series the 7 deadly sins, the 6-key learning of DotCom companies and how they deal with this change, and describe what we can learn from digitalization today. What were the recipes of the big technology groups? In the coming weeks he will describe such recipes in more detail here in the blog.

Part 2: Radical orientation towards customer behaviour. Healing own deficits through M&A and why takeovers to “moon valuations” actually make sense in the end.

The customer is always in focus. Is that a truism? Actually, it is! But is it lived in our industry? Rather less if you look at the digital activities of Deutschland Ag and the German banks and savings banks, which starts much too late or failed long ago. Besides the well-known examples, which I already listed in the first episode of this article series, German banks are currently in the press about the end of their Robo Advisor projects. The end of the projects cannot be due to the actual customer needs, because the independent Robos such as Scalable Capital, Liqid and co surprise with ever new success stories regarding the assets they manage.

How do DotCom companies deal with changing customer requirements, how do they compensate for product deficits and what lessons can we as observers learn from this?

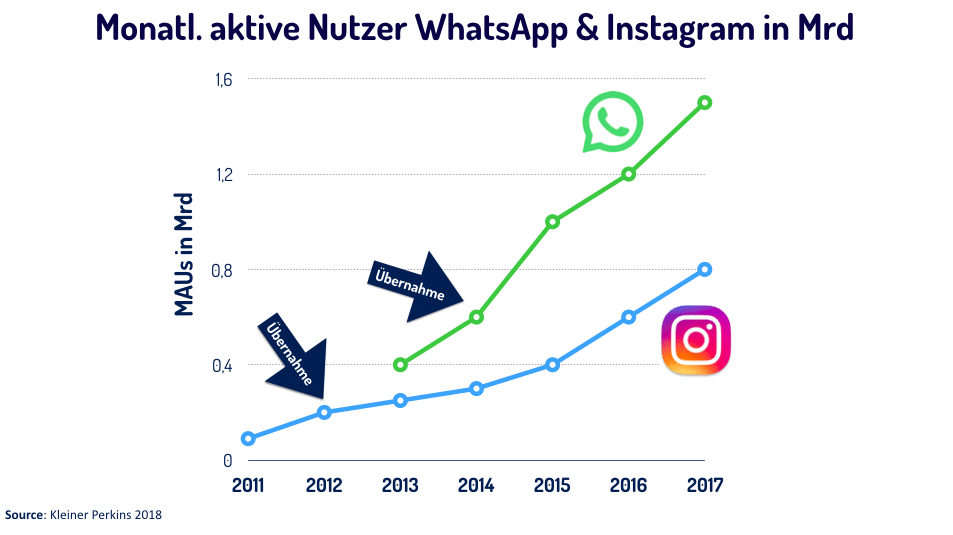

Let´s first take a look at Facebook. Facebook first made an impressive turn from the desktop browser into the mobile world and then aggressively followed its customers into the mobile app world with mobile products. Facebook also surprised with breathtaking takeovers of the then still small mobile-only providers Whatsapp and Instagram. In 2014, Facebook took over the Mini-StartUp Whatsapp for $19 billion, measured by employees. Whatsapp´s rating at the time was $42.22 per Whatsapp user. 2 years earlier at Instagram, it was similar. Facebook took Instagram for $1 billion, which corresponded to a rating of $33.33 per user at the time. Both ratings seemed extremely high at the time of the deal, mainly due to the fact that both apps were far from Facebook equal in terms of revenue per customer. Bankers would probably have claimed back then that both apps had no business model and dismissed it as an exaggeration in a bubble. But was it really an exaggeration? Both deals appear today as cheap bargains for Facebook!

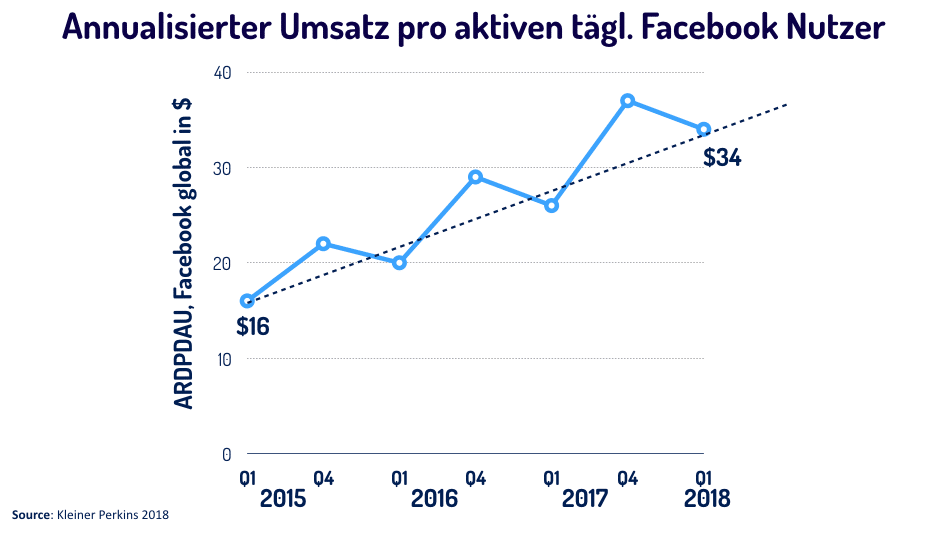

Interesting in this context is thee ratings per customer in relation to the revenue generated by Facebook itself. While Facebook still generated $16 per year with every active customer every day at the beginning of 2015, the revenue increased to $34 per customer per year at the beginning of 2018. If you extrapolate the curve, you can easily forecast revenues for the next 1-2 years. I am going to open up a simple milkmaid calculation now: Facebook has paid 2012 for every Instagram customer as much as they currently earn with these customers in the full year 2018. From this point of view, the 1 billion deal for Facebook was quite “cheap”. Even without this milkmaid calculation, the deal for Facebook seems to really pay off., because it is expected that Instagram for Facebook will very soon be the most important revenue channel for advertising.

However, the takeovers are much more relevant in the context of the Facebook Group´s corporate strategy. Facebook´s own claim is market leadership in the area of social networks. The development of the users, measured by the MAUs (monthly active users) on the platforms, shows that it was a very sensible decision to take over the potential later competitors Whatsapp and Instagram at an early stage. So these companies were “bought” out of the market before they were too big and could become a serious competitor for Facebook. What would have happened if Instagram and Whatsapp had fallen into the hands of Google (which had just discontinued Facebook´s competitor Google plus) or Apple (which was planning a social network for music with the discontinued Ping)? This would certainly have led to a more dynamic growth of one of the other competing Dot Coms in the field of social networks. Accordingly, a takeover of Instagram and Whatsapp was just as important for Facebook as it would be for a traditional bank or savings bank not to leave the topic of “mobile banking” to the independent N26s, Starlings, Revoluts alone. Do those responsible in the banks draw the same conclusions as Mark Zuckerberg? In the case of BBVA with the takeovers Simplebank (retail banking, USA) and Holvi (corporate banking, Europe), there are already exactly such example.

Another nice learning example is e Bay and the area of payment transactions. Today nobody asks the question anymore that a fully integrated purchase and payment processing is a must-have for marketplaces. All relevant mass and niche marketplaces today offer fully integrated payment processing. At the end of 1990s / beginning of the 2000s, when eBay was the dominant marketplace, the eBay management around CEO Meg Whitman understood this long ago. The non-integrated payment processing was a source of constant customer problems. To solve these problems, eBay took over the payment StartUp Billpoint from WellsFrago Bank in 1999. They paid almost $50 million for the StartUp and integrated it into their US marketplace as a payment method. A battle then began on the eBay marketplace between the independent and nimble StartUp PayPal and the integrated eBay corporate solution Billpoint, which is described in a highly readable book by early PayPal CMO Peter Jackson. PayPal evolved as the preferred solution for eBay users. Both merchants and customers preferred it to Billpoint, the long-forgotten eBay corporate solution. How did eBay react? Did you double your investments in your own solution in a “now-first-right” mentality, or did you bow to the customer and drop Billpoint in favour of PayPal?

Local banks and savings banks react with their “well-performing” digital solutions on comparable situations with the stubborn “now even more so” approach or statements such as: “The solution has no alternative”. But eBay listened to the customers at the time and took over Pay Pal for $1.5 billion only two years after the Billpoint acquisition. Michael Moritz, the partner of PayPal investor Sequoia, told years later from the sewing box at an executive event of PayPal: “The PayPal IPO at that time was only possible because the eBay management and the PayPal investors could not agree on purchase price. The IPO was therefore the way out of a “neutral” valuation and eBay took over PayPal with a premium of 77% of the market price immediately after the IPO, delisted the PayPal share and the rest is history.

Paypal itself repeated this early and successful eBay strategy several times. There were takeovers in all the segments where PayPal itself fell behind the market:

- The online sales financier BillMeLater was acquired for 1 billion in 2010 because PayPal Credit did not perform and BillMeLater was preferred at Amazon, Overstock and co.

- The P2P payment method Venmo was taken over together with the online PSP Braintree 2013 for $800 million because PayPal had fallen behind in its own P2P payment.

- In Europe, the first PayPal acquisition in 2012 was the German BillSafe purchase startup. Reason: Bringing BillMeLater to Europe was more expensive than taking over the Earlystage StartUp in Germany and the Nordic market leaser attacked PayPal in Germany

- A few weeks ago, the takeover of the Swedish MIPOS provider iZettle generated headlines for $2.2 billion. Here, too, the reason: The implementation of the in-house product PayPal Here was “sub optimally implemented” and simply not successful on the market.

The examples of Facebook, eBay and PayPal are just a few examples of many others where Internet companies are responding to changing consumer behaviour through M&A. Faster, more innovative companies, which are very close to the core product, have proven traction, and could become serious competitors, have been and are (expensive) taken over. At the same time, corporations, including credit institutions, in Germany invest only “small change” in minority shares of many early-stage start-ups with often unproven business models or sink significant amounts of money into in-house digital projects, which often come to the market too late and have not been and are not managed entrepreneurially. Who has the better strategy? The conservative mixture of the cautious investment and in-house projects or expensive takeovers of proven business models with traction from which serious competitors can emerge? The role models from Silicon Valley speak a clear language.