On Monday morning, colleague Heinz-Rogier-Dohms surprised the financial scene with his newsletter with a side note that was probably overlooked by many readers due to the news of the Deutsche-Commerzbank mergers. The German stock exchange discontinues its joint venture (JV) with the Naga Group for a marketplace for digital gaming products (in the jargon In-Game Items). Look financial scene: „Exclusive – the German stock exchange withdraws from bizarre Fintech joint venture“.

The German stock exchange has returned its 40% stake in JV to Naga. The cooperation was announced extremely offensively and euphorically by the German stock exchange using many superlatives in 2016, as only known only from StartUps. Until very recently, the press release from that time was still on the corporate page of the German stock exchange, because it can be found high up in the Google Index even with the initial text, when searching for the name of the platform „Switex“. Today, one click leads to an error message. Did one delete the press release quickly after the research of colleague Dohms and does not stand up to their own past?

„It won’t work“

A report worth reading about the announcement at the time of the entry into the huge „46 billion mark with 10% growth per year“ without a concrete gaming cooperation partner, with quotations from the project participants German stock exchange, Deloitte and Naga which can still be found in the Swiss blog Fintechnews.ch. Already during the announcement, expert market observers scratched their heads over where the project participants see the real business potential. Worth listening is the December 2016 edition of the microeconomist podcast and the comments and evaluation of the announcement from minute 52. Sobering conclusion at the time: „Won’t work“.

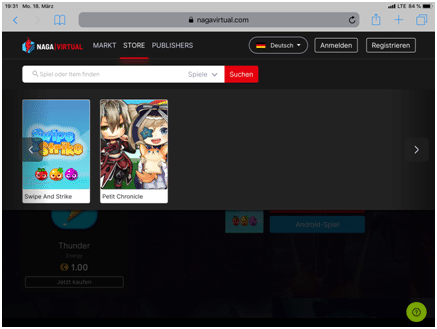

A look at the Switex marketplace, which has since been renamed Naga Virtual, unfortunately shows today a rather manageable range of only two rather unknown games.

Source: Screenshot www.nagavirtual.com

Since probably hardly any of our readers spend their time here in the blog with computer games, here’s a brief explanation of what it’s all about: Driven by the innovative and successful German game start-ups at that time, also called publishers, Bigpoint, Innogames, Goodgames and Gameforge and others, the general monetization of computer games has changed massively. In the past, a game was bought for a unique price (called boxgame in technical jargon) in electronics stores. Today, the price model has changed to the so-called „free2play“ concept for almost all mobile smartphone games.

Closed Marketplaces

There the game itself costs nothing, but the player has to buy an individual game currency later in order to buy so-called „items“. An item can be a special sword, armor or just a different kind of look of the digital avatar. At one-point, individual providers such as World of Warcraft or the gaming platform Steam started with closed marketplaces for the purchase or exchange of such items. Interesting anecdote on the side: Steam had engaged Yanis Varoufakis as an external consultant for their own price strategy before he became the Greek finance minister and the opponent of Wolfgang Schäuble during the negotiations of the euro rescue packages for Greece.

Trading on these two closed platforms is still very successful today in the special niche. A few years ago, a computer game was by far the biggest user of the PayPal function Mass Payment in the USA.

Thus, PayPal allows a special form of mass transfer of an amount, with one transaction to thousand PayPal accounts of the players, at the same time. Mass Pay was used to pay out game currency in USD.

The many mistakes of the stock exchange platform

The idea of the joint venture was now to open the tradability on a regulated marketplace of the German stock exchange. Unfortunately, the makers of the marketplace have conceptually ignored some very obvious basic facts:

Gaming providers in Europe who allowed trading and, if necessary, payment in cash of their virtual currency, long ago fell under the requirement of the Payment Service Directive. The above-mentioned publishers would have to obtain a ZAG license from BaFin in order to join a marketplace, just like the one the stock exchange had in mind. Steam & Co, which today offer closed marketplaces, are based in the USA and therefore do not fall under the European Payment Service Directive. How probable was it that the German gaming champions obtained a ZAG license „only“ so that their items could be traded on a third-party stock exchange?

The large volumes in gaming are usually now issued mobile, i.e. in the Apple App Store or Google Play Store. The rapid change to gaming mobile, has also caught the well-known browser gaming champions on the wrong foot, long before the launch of the stock exchange platform, as can be seen from Bigpoint, Goodgames and Zynga, for example.

„The shift from gaming to mobile has got the browser gaming champions on the wrong foot.“

Game balancing is an important factor in keeping a game attractive. If too many items flow out of or into a game through an external stock exchange, or if users migrate from game A to game B on a massive scale, for example, the game balancing is endangered and with it the attractiveness of the game itself. Also, here: How great is the added value for a publisher to support an external marketplace vs. the danger of losing their own attractiveness?

A certain intransparency of the actual values in the game and the items is quite wanted by the publishers. The participating publisher would rob himself of this, in a transparent marketplace. And why should he do that?

Last but not least: A similar initiative by Amazon to buy game items on its own marketplace had already failed before the launch of the platform in Europe and today is limited to the sale of vouchers for games and game platforms. If even Amazon, despite customer market power, media competence and its distribution via its own game streaming platform Twitch, with 140 million active users per month, fails in the face of such a model, where does the market foreign German stock exchange get the confidence to do it better?

A certain intransparency of the actual values in the game and the items is quite wanted by the publishers. The participating publisher would rob himself of this, in a transparent marketplace. And why should he do that?

Last but not least: A similar initiative by Amazon to buy game items on its own marketplace had already failed before the launch of the platform in Europe and today is limited to the sale of vouchers for games and game platforms. If even Amazon, despite customer market power, media competence and its distribution via its own game streaming platform Twitch, with 140 million active users per month, fails in the face of such a model, where does the market foreign German stock exchange get the confidence to do it better?

Post-Mortem-Analysis

In this blog and podcast, we always encourage corporates to try out new ideas and, of course, allow them to fail. So, it was good that the German stock exchange had the courage to break new ground. But it is difficult when all the facts from the industry clearly give a signal that such an initiative will at least have an extremely difficult time. If things are simply „wanted“ too much politically, then sometimes the facts only disturb – just postfactual times.

Should one now have the same gloating joy about the failure of the German stock exchange as some corporate managers do when a start-up with real entrepreneurial risk fails? NO. We have another chapter that can be added to the multitude of stumbling local corporate tech initiatives.

Hopefully the right conclusions will be drawn from this in the individual houses – startups and the US tech companies with their error culture create a post-mortem analysis, in such cases, so that the errors are not made again. Hopefully next time, more will listen to the experts and less to the politicians.